JEWISH HOLIDAYS

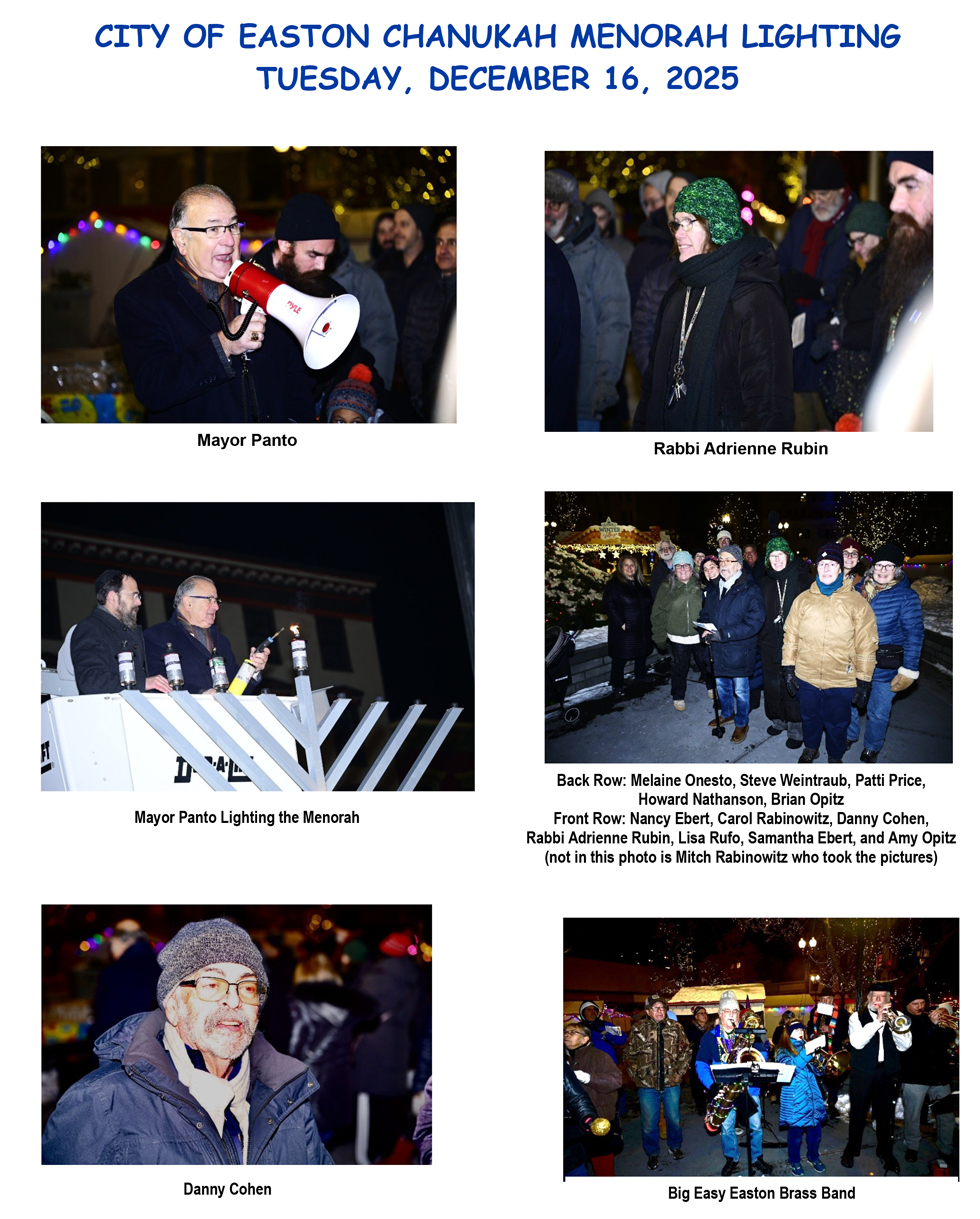

HANNUKAH LIGHTING 2026 - CITY OF EASTON

RITUAL MESSAGE - JANUARY 2026

Many of our Jewish rituals originate from mitzvot, including the mitzvah to care for the needs of the community. Part of Leviticus 19:8 states: "you shall love your neighbor as yourself." It is amazing how many of us perform this mitzvah every day within the Jewish community and the communities at large. A few weeks ago, Donna Stamets held an end-of-year party for her friends, members of her women's auxiliary, and her weekly bingo volunteers. Among the guests were several Bnai Shalom members who supported her bingo in some capacity.

In celebration of communal support and cooperation, we will again come together at Bnai Shalom on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day on Monday, January 19 at 11:00 A.M., to participate in the recitation of his Letter from the Birmingham Jail. The Jewish community was a big supporter of Dr. King and his message. This is just another example of the power of what loving your neighbor as yourself could accomplish. Per Andrew Gold who wrote in 1978, "Thank you for being a friend."

Am Yisrael v' Bnai Shalom Chai, Howard Nathanson, Ritual Chair